Minimum query is 3 letters.

JURAJ HERZ: LAUGHING THROUGH THE HORROR

by Irena Kovarova

The singular career of the prolific film director and occasional actor Juraj Herz is without parallel in the context of the cinema emerging from Czechoslovakia starting in the mid 1960s. He was a breed apart and decidedly a filmmaker of excess—in his visual style and art direction, as well as in the abundance of horror and eroticism in his genre-bending dark comedies, fairy tales, and dramas. Under the surface of genre, he smuggled in clear-eyed and engaged social and political commentary, while attaining the heights in his mastery of the formal language of cinema.

Herz entered the Prague scene at the same time as the core group of filmmakers of the Czechoslovak New Wave, but never truly considered himself one of them. But even if he personally operated on its margins, his most important film, the psychological horror THE CREMATOR, and a number of his other works, fall squarely among the best films of the Wave and address the same issues. This led censors to intervene often, but being one of the most bankable film directors in the country assured him work, apart from a few brief spells, throughout his career.

His penchant for the macabre, his gothic style, and his examination of the underbelly of the human psyche made Herz a darling of the fantasy and horror film scene, and in the past couple of decades his films have achieved cult status among genre film geeks in Europe and the U.S. alike.

A polyglot—a quintessential “Mitteleuropa” man—Herz was born in 1934 into a Slovak-Hungarian-German-Jewish family in Kežmarok (now Slovakia). He mastered all of these languages, along with Czech and Polish, which he absorbed together with the arts. The horror of the Holocaust—which he experienced as a child, at first living in hiding before being transported with his family to the concentration camps—seeped through into his films, which set him apart from his filmmaking peers. Yet the experience didn’t rob him of his joie de vivre, possibly thanks to the fact that everyone in his immediate family was lucky enough to survive.

While his eye was trained in photography studies in Bratislava, even then he was already drawn to theater and cinema. Acting was Herz’s calling card to Prague’s theater school of the Academy of Performing Arts (DAMU). Studying directing and acting in puppet theater, he befriended Jan Švankmajer, who ended up in the same department. The two men were bound by more than one thread: Born on the exact same day, they shared a dark and wicked humor and a predilection for the obscure. Švankmajer was already steeped in surrealism by then, and served as Herz’s conduit to it. They worked on performance ideas while serving together in the army and staged them at Semafor theater upon their return to Prague. Herz acted in two of Švankmajer’s early films, while Švankmajer and his wife, Eva, contributed art to Herz’s works later on—who else to better design and so vividly the guts of a killer car (FERAT VAMPIRE) or the disembodied hearts in the fairy tale THE NINTH HEART, which Eva Švankmajerová created the poster and opening credits for.

The Film Academy—the venerable FAMU—was Herz’s dream, though. Since he was enrolled in another school, he wasn’t allowed to attend the screenings of non-distributed films from the West and the East held exclusively for film school students. But he often sneaked in, and even if sometimes he was embarrassingly expelled by the projectionist, he succeeded in soaking in much of the French avant-garde and Italian neorealism. Along with Polish directors such as Wojciech Has, his favorites were the Yugoslav Black Wave, Dalí, and especially Fellini.

The same way he snuck into the FAMU screening room, Herz snuck into filmmaking through the back door of acting, which led to his assisting older directors at Barrandov Studios. Notably, he assisted Kádár and Klos on the Oscar-winning Holocaust drama THE SHOP ON MAIN STREET. His first film-directing opportunity came through Jaromil Jireš, who invited him to take part in PEARLS OF THE DEEP, the omnibus project based on Bohumil Hrabal’s book. The resulting short, THE JUNK SHOP, didn’t make it into the final film—now considered the manifesto of the Czechoslovak New Wave—supposedly due to its length. But Herz believed it was because he wasn’t considered an equal, but rather “just some puppeteer making a film” (while Ivan Passer, whose short also didn’t make the cut, “was just too kind”). Still, Herz’s contribution, which was based on the most biographical of the stories in the bunch—and which he shot in a recycling collection shop where Hrabal had actually worked—opened the door for him to direct his first feature film, the whodunit murder mystery SIGN OF CANCER. This psychological probe of life inside a hospital immediately made him a target of censorship and criticism, but after a renowned physician confirmed that whatever Herz depicted about the medical field was largely (and unfortunately) based on the truth, his career as a director was ready to take off.

And so it did. In quick succession, he created several of his finest works. The unnerving THE CREMATOR, equal parts nauseating and provoking uneasy laughter, masterfully portrays the mind of a psychopathic opportunist serving an immoral ideology. Never clearly identifying it as Nazism, Herz intended it also to refer to the ideology that was bringing his country to its knees and leading its people down the slippery slope of conformism. Among the films that followed were his fin-de-siècle decadence-themed OIL LAMPS (which in 1972 competed for the Palme d’Or in Cannes) and the gothic tale MORGIANA, both rich and dark costume dramas that completed Herz’s expressionistic period. After having several of his own projects rejected, he finally accepted scripts for more popular fare, directing a series of comedies and criminal stories that were successful at the box office. That in turn made it possible for him to come back to his own topics, subversively applying horror principles to the more officially palatable genre of the fairy tale: BEAUTY AND THE BEAST and THE NINTH HEART, shot back to back, utilizing the same set (radically transformed for each film).

But in Communist Czechoslovakia, even horror movies were not safe from the censors’ scissors, often violating the film’s integrity. This was the case for Herz’s next project, FERAT VAMPIRE, which gravely suffered at the hands of censors, who deemed its open sexuality and freely flowing blood inadmissible. We can only guess how much better the film would have been without them taking a hatchet to it. But especially thanks to the acting, it’s still an enjoyable addition to the genre: The lead roles were played by none other than Jiří Menzel, the director of CLOSELY WATCHED TRAINS and other classics, and Dáša Veškrnová, a starlet at the time, though now better known as Dagmar Havlová, the wife of the late Václav Havel, playwright, dissident and post-1989 president of Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic.

When the censors completely shut down Herz’s production of the dystopian parable MAGPIE IN THE HAND (which only saw the light of day after the regime change), he started losing energy to continue under those conditions. He did manage to direct a film into which he channeled his experience from the concentration camps—CAUGHT BY NIGHT, about the Communist journalist Jožka Jabůrková—after which he emigrated to Munich, in West Germany. He was based there through the mid ’90s, making films for TV and the big screen, including contributions to the Maigret series in France.

After his return to Prague, he made a number of horror films, as well as comedies and dramas setting the record straight on historical injustice—PASSAGE, T.M.A., BLACK BARONS, and HABERMANN, to name the key works. Unlike directors such as Věra Chytilová, who made just one foray into horror with WOLF’S HOLE, Herz and Švankmajer stood alone on the Czech scene in devoting themselves to the dark genre throughout their lives. Directing over forty feature-length works for the screen and TV in his career spanning five decades, Herz often also cowrote as well. As an actor, he portrayed twenty roles in films by other directors, and more than ten times he directed himself in his own. Much of the last two decades of his career, he spent involved with his second love, the theater, which gave him the opportunity to direct fifteen productions for the stage, including an opera for the National Theater in Prague. He passed away less than a week after Miloš Forman, in April 2018, at the age of 83, while this touring retrospective was already in production.

Herz’s all-consuming interest in genre films made him a party of one in his country. Although most of his works were not examples of straight-up horror, with its kitsch and bloody gore—he opted for lightening the mood with humor, adding sarcasm and reflections of society’s ills—he nonetheless remains a master of the art.

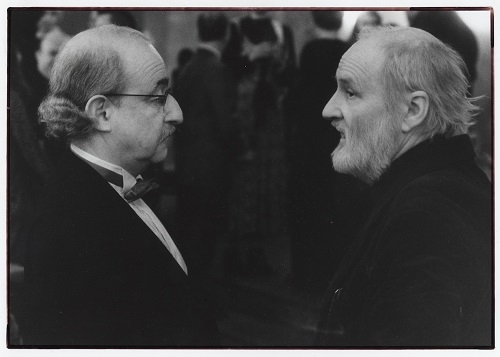

Facing his 'twin': Juraj Herz (L) and Jan Švankmajer (R), born on the same day. Photo taken at Czech Lion Awards ceremony, Prague (Lucerna Palace) March 1, 1997. Photo by Miloš Fikejz ©

>>>

THE JUNK SHOP (Sběrné surovosti, 1965)

A work of nonstop invention set over the course of a single day at a paper recycling facility frequented by oddballs, including manager and aesthete Bohoušek, based on Bohumil Hrabal's life and a story from his book Pearls of the Deep.

THE JUNK SHOP (Sběrné surovosti, 1965)

A work of nonstop invention set over the course of a single day at a paper recycling facility frequented by oddballs, including manager and aesthete Bohoušek, based on Bohumil Hrabal's life and a story from his book Pearls of the Deep.

SIGN OF CANCER (Znamení raka, 1966)

A warped detective story that begins with a murder in a hospital, the investigation of which reveals rampant incompetence, the film’s implicitly critical depiction of a public service sector overloaded with underqualified Party stooges would land Herz in trouble with censors for what was not to be the last time. New subtitles!

SIGN OF CANCER (Znamení raka, 1966)

A warped detective story that begins with a murder in a hospital, the investigation of which reveals rampant incompetence, the film’s implicitly critical depiction of a public service sector overloaded with underqualified Party stooges would land Herz in trouble with censors for what was not to be the last time. New subtitles!

THE CREMATOR (Spalovač mrtvol, 1969)

Herz's masterpiece, in a new digital restoration released by Janus Films in North America, is set in 1930s Prague, where Nazi ideology hangs as thick as the charnel fumes over the crematorium run by the troubled Karel Kopfrkingl. This macabre and harrowing work of psychological and social breakdown was banned after its 1969 debut only to re-emerge and garner deserved praise twenty years later.

THE CREMATOR (Spalovač mrtvol, 1969)

Herz's masterpiece, in a new digital restoration released by Janus Films in North America, is set in 1930s Prague, where Nazi ideology hangs as thick as the charnel fumes over the crematorium run by the troubled Karel Kopfrkingl. This macabre and harrowing work of psychological and social breakdown was banned after its 1969 debut only to re-emerge and garner deserved praise twenty years later.

OIL LAMPS (Petrolejové lampy, 1971)

Contender for the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1972, this early 20th Century period piece is set in a provincial town, Jilemnice, that’s riven by repressed desire and smoldering secrets. Herz plumbs deep within the psychology of his characters in this gripping and gorgeous film, which investigates the rot beneath the decoration and decorum of the Secession era. New subtitles!

OIL LAMPS (Petrolejové lampy, 1971)

Contender for the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1972, this early 20th Century period piece is set in a provincial town, Jilemnice, that’s riven by repressed desire and smoldering secrets. Herz plumbs deep within the psychology of his characters in this gripping and gorgeous film, which investigates the rot beneath the decoration and decorum of the Secession era. New subtitles!

MORGIANA (1972)

A Gothic drama about two sisters, Klára and Viktorie—both played by Iva Janžurová, in an amazing double-role performance—are put at loggerheads when the sweet, vapid Klára receives the better part of their father’s sprawling estate and the love of the man that Viktorie adores, leading the spurned sibling to venomous thoughts of murder.

MORGIANA (1972)

A Gothic drama about two sisters, Klára and Viktorie—both played by Iva Janžurová, in an amazing double-role performance—are put at loggerheads when the sweet, vapid Klára receives the better part of their father’s sprawling estate and the love of the man that Viktorie adores, leading the spurned sibling to venomous thoughts of murder.

BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (Panna a netvor, 1978)

A tale you’ll know well—innocent girl presents herself as sacrifice to a cursed, freakish beast living in isolation, and learns to live with and love her captor—but turned into something very different in Herz’s morbid imagining. New subtitles!

BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (Panna a netvor, 1978)

A tale you’ll know well—innocent girl presents herself as sacrifice to a cursed, freakish beast living in isolation, and learns to live with and love her captor—but turned into something very different in Herz’s morbid imagining. New subtitles!

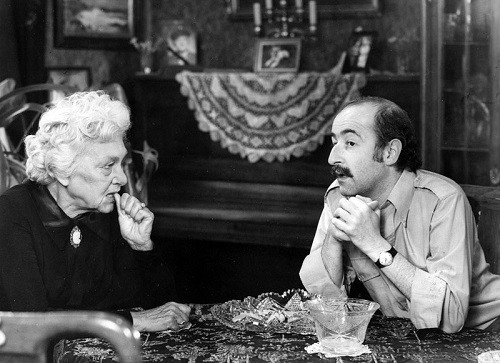

FERAT VAMPIRE (Upír z Feratu, 1981)

A satire on consumerism, a potent piece of anti-automobile propaganda, and perhaps the purest horror exercise that Herz produced. Starring the excellent Jiří Menzel (the Oscar winning film director) in the lead role of Dr. Marek. New subtitles!

FERAT VAMPIRE (Upír z Feratu, 1981)

A satire on consumerism, a potent piece of anti-automobile propaganda, and perhaps the purest horror exercise that Herz produced. Starring the excellent Jiří Menzel (the Oscar winning film director) in the lead role of Dr. Marek. New subtitles!

CAUGHT BY NIGHT (Zastihla mě noc, 1985)

Conceived as a biography of Communist journalist Jožka Jabůrková, a victim of Ravensbrück, Herz went his own way, creating a nauseously stylized vision of hell on earth that is, with Wanda Jakubowska’s 1948 The Last Stage, one of only two fiction films made by a camp survivor about the experience.

CAUGHT BY NIGHT (Zastihla mě noc, 1985)

Conceived as a biography of Communist journalist Jožka Jabůrková, a victim of Ravensbrück, Herz went his own way, creating a nauseously stylized vision of hell on earth that is, with Wanda Jakubowska’s 1948 The Last Stage, one of only two fiction films made by a camp survivor about the experience.

GOLDEN SIXTIES: JURAJ HERZ (Zlatá šedesátá, dir. Martin Šulík, 2009)

An illuminating portrait of Juraj Herz from a 27-part TV series about masters of the Czechoslovak New Wave.

GOLDEN SIXTIES: JURAJ HERZ (Zlatá šedesátá, dir. Martin Šulík, 2009)

An illuminating portrait of Juraj Herz from a 27-part TV series about masters of the Czechoslovak New Wave.

COMEBACK COMPANY

For press and booking inquiries:

To sign-up for our newsletter

email us with "newsletter" in the

subject line:

Comeback Company 2014

Design by Parallel Practice

© All rights reserved.