Minimum query is 3 letters.

ON SKI FILMS AND FILM SCHOOL

It may surprise someone who has seen Ruben Östlund’s films Play, Involuntary, and Gitarrmongot that the director began his career making ski films. When Östlund was 22 years old, he made his very first film, Free Radicals. It was filmed in the French and Swiss Alps and at the Swedish ski resorts Åre and Riksgränsen. To the sounds of guitars and hard-core screams from bands such as the Hellacopters, Refused, and Mary Beats Jane, skiers dressed in neon clothing and shiny skiing goggles hurl themselves down steep slopes, do advanced jumps, contend with snowslides they themselves have caused; sometimes they even disappear in the snow and twirl around as they fall hundreds of meters down the slopes. And every now and then, short scenes from the skiers’ everyday lives are shown.

When Östlund applied to Filmhögskolan (the School of Film Directing) in Gothenburg in 1999, he submitted Free Radicals and other ski films as his admission application. The school had been founded only a few years earlier by Göran du Rées, who himself was a director and cinematographer, and his inspirations for the education the school would provide were Italian neorealism and the French New Wave. Filmmaking was no longer supposed to be about creating a story but about “portraying reality.” “Every situation has its observer” was the motto. Du Rées himself phrased the mission of the school as to “not educate cannon fodder for the media army but train samurais.”

According to du Rées, both he and the entire admissions board were astonished when they saw Östlund’s films. Even though they were ski films, which are rarely seen within the art world, they were “incredibly strong.” All of them were technically well-made, with takes that could last several minutes, and at the same time, du Rées felt, they were about “real people.”

Östlund was accepted. Roy Andersson, who had just returned to the world of film and been praised for Sånger från andra våningen (Songs from the Second Floor), had received an honorary doctorate from the school. However, the school was still viewed as an underdog in the Swedish film world; it was smaller and younger and had a completely different philosophy from the notable Dramatiska Institutet (Academy of Dramatic Arts) in Stockholm. Both inside and outside the classroom, there were ongoing discussions about why, not how, you make film, and at the end the conclusion would always be that film should be constructive for society. The students were encouraged to create films that went in a completely different direction from the traditional stories, with the intention of changing something in society.

Östlund was inspired by people like Andersson, du Rées, and Kalle Boman, who had produced films for Andersson, Bo Widerberg, and Marie Louise Ekman. Östlund left the ski world behind and traded a life of dangerous ski slopes for quiet depictions of people. As his graduation project, he made a documentary about his parents’ divorce, and during his final school year he started his own production company, Plattform, with his classmate Erik Hemmendorff.

ON GITARRMONGOT

Ten years ago [in 2004], when Östlund made his debut as a director with Gitarrmongot, which consists of a series of longer scenes in which the viewer gets to follow a group of odd people, many critics claimed his style was similar to Roy Andersson’s.

Ruben Östlund: It made me very upset that, as soon as a person who differed from the norm had a leading part in a film, it had to be motivated by the fact that he was brilliant at playing the piano or had some other unique talent. It was as if reality was filtered to make sure it would not upset the audience. The Gitarrmongot was supposed to differ from what you would normally see at the cinema. I wanted the viewer to be conflicted about it and ask: “What the hell am I watching? Is this a documentary or is it fiction, how am I supposed to relate to the story, and what does the director really think about this?” Therefore, it was very important that the film be shown in cinemas, because that would mean that the critics would have to sit down and write something about it. If a film is only shown at a film festival, it easily becomes marginalized, but if it is shown in cinemas, people have to find a way to deal with it. Then Nils Petter Sundgren would have to write something about it.

Q: The attendance figures for Gitarrmongot were around 3,500.

I still believe that a film like this has a much longer life span than the short period of time it is actually shown in cinemas. A film about Sune [a character from a popular Swedish book series for youths], or whatever else it could be about, might be seen by two, three hundred thousand, but then after a few years it will be forgotten, whereas people will remember a film that demands more of the viewer. Gitarrmongot is still shown all over the world; for example, it will be shown at a film festival in Ljubljana this fall. When Michael Haneke was asked if it bothered him that very few people actually saw his film Amour, he simply answered: “Das ist mich total egal”—it’s irrelevant to me. I believe that’s how you feel when you are confident in your vision.

Q: At the same time, the low figures almost cost you your next project, as they made it very hard for you to get it financed.

Our film commissioner from the Swedish Film Institute didn’t like Gitarrmongot at all, so when Erik and I went to present Involuntary, he had already decided he would reject the idea. But we did something really cocky and claimed the premiere would be at the Cannes Film Festival, and asked him: “Do you want to be a part of this or not?” Suddenly, it would be too risky for him to say no.

Q: It sounds like it was pretty risky for you as well.

Already when Erik and I were in film school, we realized that many producers are not interested in the ideas you have, they are more interested in whether they can get a grant for the project. They also always have five other directors lined up waiting to get the chance to make a film. Producers take on many projects to keep their business running, but very few of them actually become films. That’s why we started Plattform Produktion. Having our own production company meant that we were free to decide whether to start a project or not, even if we didn’t have financial support for it yet. Economically, it’s risky, but at the same time I think it is better than having to ask a film commissioner: “Do you think we should make this film, or that one?”

ON INVOLUNTARY

Q: Involuntary also seemed to stir up emotions in the audience.

After the Swedish premiere at the Stockholm Film Festival, there was one man who stood up and was extremely upset: “What is this? Where did you study film?” I didn’t understand why he was so angry, so I calmly replied that I went to Filmhögskolan (the School of Film Directing) in Gothenburg. “And what the hell did they teach you there? Where is Ingmar Bergman? There’s absolutely nothing of film history in this movie!”

Q: People thought the man’s outburst was staged.

I can understand why people thought it was staged, because it was very easy to respond to his critique: “When Ingmar Bergman’s films were first released, people didn’t respond to them as they do today. Many of his films were actually believed to be challenging film history.”

ON PLAY

My idea when filming Play was to create a film that would force the viewer to reflect and then form an opinion. The intention wasn’t that people should accept the fact that the robbers are black, but rather to start a debate about why they are black. People don’t often think about this when making a film, so most of the time they are unaware of how they choose to portray people with different skin color.

Q: Did you know that the film would be debated to such a great extent?

I was definitely aware that I was walking in a minefield when I made it, because it was my intention to provoke. It was very hard for me, since I was not used to being in the middle of such debates. I felt like a boxer, who went into the ring, got hit, and became extremely dizzy. Psychologically, it was very demanding, but afterward I came to think of it as a good experience.

Q: One of the objections against Play was that it was counterproductive and reproduced stereotypes rather than starting a debate about them.

I absolutely believe that’s something to think about. To me, it’s reasonable to put into question whether the film is confirming the usual images of the stereotypes or if it’s doing something else. In my opinion, the film isn’t counterproductive, and it’s important because it asks the viewer certain questions. I also believe that the provocation it caused forced people who wouldn’t normally discuss this to speak up about their opinions, which made the discussion break new ground.

However, it was mostly cultural journalists who analyzed the film. Did it really inspire other people to speak up?

The debate didn’t end with the discussion about this film. I see Play as being part of a movement, and many great things has been done since it was released

[…]

I was watching Iron Man 3 with my kids the other day. It’s about the gun industry, and it legitimizes the use of weapons in the fight against terrorism. And the terrorists look exactly as they’re supposed to in American films, but we don’t discuss that type of reproduction of stereotypical images at all. We don’t say, “What the hell is this fucking image?” But it was the most popular film in cinemas for a very long time.

People seem to think that just because film is meant to be entertaining, it won’t have an effect on reality. But how you choose to categorize a film doesn’t control the effect it will have on the viewer. The human being isn’t controlled by reason; we imitate behavior. The images that have the greatest distribution are the ones that will influence us the most. That doesn’t mean that the commercial film industry shouldn’t be able to create the images they want, only that it should have political consequences. We need to understand the potential of an image and learn how to use it in a more effective way—for example, its ability to show other people’s opinions and experiences could be very useful. In that aspect, the image surpasses everything—the written word doesn’t even stand a chance.

ON FORCE MAJEURE AND FILMMAKING

Q: Since you’re always very open about your goals, how does it feel when you fail to reach them? For example, you were hoping Force Majeure would be in the competition for the Palme d’Or, but instead you were competing in Un Certain Regard.

It was a disappointment that we were not in the competition for the Palme d’Or. Though you have to keep in mind what happened afterward. Many in Cannes asked why it wasn’t in the competition, and I think the management gave a very good answer: “It must be better to be able to ask that than the opposite: ‘Why is this film in the competition?’” And we said that next time we’re definitely going to be competing for the Palme d’Or.

[…]

My point is not that the nuclear family should be opposed in any way, but rather that it should be debated. It is also exciting to explore what would happen if a man were stripped of all refinements and instinct kicked in.

I think it would be hard to make a film that is both commercial and poses a question. A film with a story that is meant to explore unknown territories wouldn’t normally attract a big audience during the short time it’s shown in cinemas. It needs more time in order to have an effect. It’s like simple and complex carbohydrates.

Q: So what’s it like being a complex carbohydrate?

It’s good, especially when you get the opportunity to take part in prestigious events such as the Cannes Film Festival. It’s a fucking luxury to work in Sweden compared to other countries. For example, my American friends, who are interested in making the same kinds of films as I am and who have also had their films shown at the Cannes Film Festival, have to conform to completely different rules.

ON A POSSIBLE FUTURE PROJECT, A MONKEY FILM

Q: That sounds exciting, but not exactly like a film that would be competing for the Palme d’Or.

Sure, if the Palme d’Or is my goal, then I probably shouldn’t do that project. However, it’s so different from everything I’ve ever made: not working with dialogue but instead filming someone playing a monkey, which is so obviously theatrical. I’ve always felt both excited and insecure when I’ve started to make a new film. Perhaps that’s why I should make this project, because I feel some kind of resistance to it. When you go against the flow, rather than with it, you create energy. It’s pure physics. But if I wanted that film to be in the competition, then I would have to persuade Juliette Binoche to play a monkey.

“PATH OF MOST RESISTANCE”

by Oscar Sonn Lindell

Excerpts from an interview with Ruben Östlund

Filter Magazine, Aug/Sept 2014 issue,

translated from the Swedish by Klara Kovac

FORCE MAJEURE (Turist, 2014)

An avalanche in the French Alps sends a father scurrying for his life, leaving behind his panicked wife and children, in Östlund’s examination of the conflict between social role and survival instinct.

FORCE MAJEURE (Turist, 2014)

An avalanche in the French Alps sends a father scurrying for his life, leaving behind his panicked wife and children, in Östlund’s examination of the conflict between social role and survival instinct.

PLAY (2011)

Unabashedly impolite, Östlund’s record of racially charged harassment and societal paralysis offers food for thought and fuel for fury.

PLAY (2011)

Unabashedly impolite, Östlund’s record of racially charged harassment and societal paralysis offers food for thought and fuel for fury.

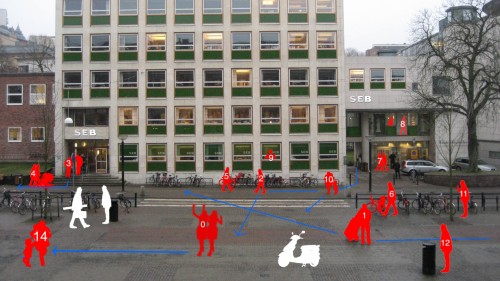

INCIDENT BY A BANK (Händelse vid bank, 2009)

Based on an actual account of a bank robbery witnessed by two bystanders across the street, Östlund’s concise study of surveillance may remind some viewers of Michael Haneke’s Caché.

INCIDENT BY A BANK (Händelse vid bank, 2009)

Based on an actual account of a bank robbery witnessed by two bystanders across the street, Östlund’s concise study of surveillance may remind some viewers of Michael Haneke’s Caché.

INVOLUNTARY (De ofrivilliga, 2008)

Described by Östlund as “a tragic comedy or a comic tragedy,” the director’s second feature draws uneasy laughter through five examinations of bourgeois group dynamics.

INVOLUNTARY (De ofrivilliga, 2008)

Described by Östlund as “a tragic comedy or a comic tragedy,” the director’s second feature draws uneasy laughter through five examinations of bourgeois group dynamics.

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SCENE NUMBER 6882 (Scen nr: 6882 ur mitt liv, 2005)

A young man has second thoughts about his boast to jump from a bridge in this penetrating critique of peer pressure and the fragile male psyche.

AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SCENE NUMBER 6882 (Scen nr: 6882 ur mitt liv, 2005)

A young man has second thoughts about his boast to jump from a bridge in this penetrating critique of peer pressure and the fragile male psyche.

GITARRMONGOT (2004)

Östlund’s mostly nonprofessional cast brings a documentary quality to this compassionate, humorous portrait of outsiders and nonconformists, focusing in particular on the titular musician, a young man facing dire obstacles in life.

GITARRMONGOT (2004)

Östlund’s mostly nonprofessional cast brings a documentary quality to this compassionate, humorous portrait of outsiders and nonconformists, focusing in particular on the titular musician, a young man facing dire obstacles in life.

COMEBACK COMPANY

For press and booking inquiries:

To sign-up for our newsletter

email us with "newsletter" in the

subject line:

Comeback Company 2014

Design by Parallel Practice

© All rights reserved.