Minimum query is 3 letters.

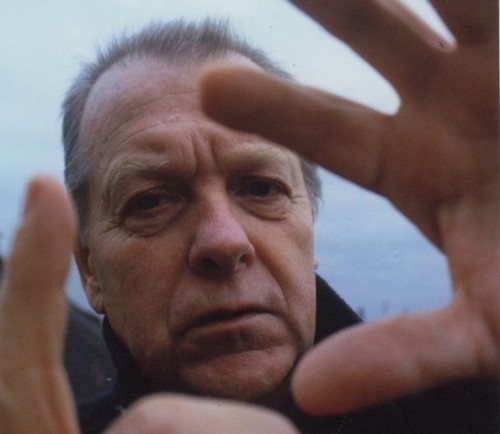

THE FILMS OF JAN NĚMEC

TOURING RETROSPECTIVE

NOVEMBER 2013–APRIL 2014

THE PARTY AND THE GUESTS (O slavnosti a hostech, 1966) courtesy of National Film Archive, Prague

The first full-career U.S. retrospective of Czechoslovak New Wave enfant terrible Jan Němec premiered in New York at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (presented by BAMcinématek) before embarking on a tour throughout North America. This survey of Němec's nearly 50-year career of uncompromising work featured 12 films, including a brand-new 35mm film print of Diamonds of the Night.

Curated by Irena Kovarova and produced by Comeback Company in partnership with the National Film Archive, Prague, Aerofilms, and Jan Němec–Film. The premiere screening of the retrospective at BAMcinématek was presented with financial support from the Czech State Fund for Cinematography.

The retrospective of director Jan Němec (b. 1936) was a long-overdue survey of work by a representative of the Czechoslovak New Wave of major import. The retrospective was one of many that BAMcinématek has devoted to Czech cinema and the New Wave in particular: a series showcasing this period of Czech cinematography was one of the major events organized by BAMcinématek in its initial year of operation, followed by other groundbreaking series, such as the first-ever retrospective of František Vláčil on American soil, held in 2002 and praised by Michael Atkinson in The Village Voice as “one of the most inspired subjects to a metro-retro in years.”

The long time it took a New York or any other U.S. film venue to explore Němec’s oeuvre is rather surprising, as it was the triumvirate of Jiří Menzel, Jan Němec, and Miloš Forman that became the face of the new cinema rushing out of Czechoslovakia in the mid-1960s, with Věra Chytilová, Ivan Passer, and Juraj Herz coming close behind them. But even at that time recognition for their work was not always immediate; because of the way the Czechoslovak state authorities provided films for international festivals and markets, sometimes it took two or three years before a film was available in international forums.

Thus, New Yorkers did not get to see Němec’s debut feature Diamonds of the Night (1964) – described by critics as a work of an “artist of tragic vision” (Pierre Philippe), an “anatomy of [the] human mind,” and as an example of Pure Cinema – until the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) mounted a survey of the Czechoslovak New Wave in 1967 (opening with a tribute to Věra Chytilová and her Daisies). Premiering internationally in competition at the Mannheim film festival, Němec’s first film immediately brought praise to the 28-year-old filmmaker, and it was shown the following year in the Cannes Critics’ Week selection. After screening at MoMA, Diamonds received a commercial release in the United States by Impact Film in 1968. Renata Adler described it, oddly, as a realistic film in her lukewarm New York Times review, whereas Michael Atkinson calls Diamonds “lean and mean” and his “favorite all-time Czech film” (Viva Mabuse! blog). For Peter Hames, the British scholar and author of the authoritative eponymous book on the Czechoslovak New Wave, the most attractive feature of Němec’s unjustly neglected early works is their urgent individuality.

The historical events of 1968 in Czechoslovakia (specifically, the democratization process culminating in the so-called Prague Spring and the subsequent clampdown by the invasion of Soviet and Warsaw Pact armies in August) heightened the world’s attention to the country’s filmmakers even further. In 1966, Němec made The Party and the Guests, which outraged the authorities who quickly banned it. However, the Prague Spring allowed for his and other films with similar fates, like Forman’s The Firemen’s Ball, to be seen and celebrated abroad: Forman, Němec, and Menzel (with Capricious Summer) were all invited with these films to compete for the Palme d’Or in Cannes. But the strikes and protests of French filmmakers shut the Cannes festival down before the jury could decide about the awards, and none of the Czechs got their chance to win and be celebrated (to Němec’s dismay – he still considers this event as robbing him of an opportunity to break out on the world scene). Less than a month after their country was invaded, this same trio presented their films in the main slate of the New York Film Festival. In addition to the three features selected for Cannes, the festival also included Němec’s 1968 short film Oratorio for Prague (which depicted the invasion), pairing it with Forman’s The Firemen’s Ball in the closing night slot, which Renata Adler praised in her New York Times review as “by far the finest movie program showing at that moment anywhere in New York.” No surprise then that both of the films were released together commercially soon thereafter.

Němec’s last film to be theatrically released in America (in 1969) was Martyrs of Love (1967), which became one of the first films distributed by Bob Shaye and his New Line Cinema, then a newcomer to the art cinema world. As Vincent Canby wrote in his New York Times review, it’s “a movie buff’s movie” – unsurprisingly it did not make Shaye a rich man.

Among the filmmakers of the Czechoslovak New Wave, Jan Němec and Věra Chytilová were the most inclined to experimentation and are considered to be avant-garde within the group. They shared not only a fierce attitude toward filmmaking, but also a scriptwriting partner and a very original costume and production designer, Ester Krumbachová (Němec’s muse and the first of his four wives). Writers often describe Němec’s style as surreal or Kafkaesque, and indeed the director considered Kafka his “essential author,” along with Faulkner, Camus, and Arnošt Lustig, on whose stories he based his first two films. Lustig, who later lived in exile in the United States, taught at American University in Washington, DC, for many years and several of his students became successful filmmakers (for instance, Amir Bar-Lev, who debuted with the documentary Fighter, of which Lustig is the subject). Many of Lustig’s books are autobiographical and his affecting prose on the Holocaust experience has been published in the United States and worldwide to much acclaim.

Last but not least of the reasons why Americans should know more about Němec is the fact that he lived in the United States in exile from 1977 to 1989. He was forced to leave Czechoslovakia in 1974 on a work contract leading him to Germany – much like Milan Kundera, Němec had no other choice because otherwise he would face criminal prosecution and his passport would be withdrawn. A fierce individualist and a rebel, he first incensed the authorities with his feature The Party and the Guests. As Němec said in an 1968 interview with Antonín Liehm: “If one lives in a society, which is at its core illiberal, it is the duty of every thinking man to attack this lack of liberty in every way he can.” His work on documenting the student protests in 1968 and the consequent Soviet invasion made certain that his film career in Czechoslovakia was over. After a couple of years not being allowed to direct, he bravely jumped the gun and gave notice to the Barrandov Studios before they could fire him along with a few other politically vocal filmmakers. Following three years of struggle, he was forced into exile in Germany, where he was finally able to realize a project long denied to him: the filming of Kafka’s Metamorphosis.

After arriving in the United States he escaped “the coldest winter” of New York for California, but as Němec put it he “did not have a chance [in Hollywood] without influential friends.” His filmmaking style and nonconformist personality were surely other reasons. He spent a decade in the States occasionally teaching film at universities and working as a commercial videographer. When the Velvet Revolution unfurled in November 1989, Němec took the first opportunity to go back to Czechoslovakia and arrived there with no passport on December 26, just as his distant cousin Václav Havel was sworn in as the country’s president. He immediately seized the moment and began realizing scripts he wrote during the long filming hiatus in the States. Digital cameras became endemic for his films in supporting his experimental style and allowing him to produce films independently through his own production company. Unlike many of his New Wave peers, Němec has been even more prolific since 1989 than in his early career.

(program and film notes by Irena Kovarova)

"A Czech Master Rediscovered" - Kristin M. Jones, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

"Worldview radio interview with Jan Němec and Milos Stehlik" - Jerome McDonnell, WBEZ CHICAGO

“Off the Blacklist: The Films of Jan Nemec” - Max Nelson, FILM COMMENT

"Jan Němec on jazz and making movies under communism” - Steve Macfarlane, BOMB MAGAZINE

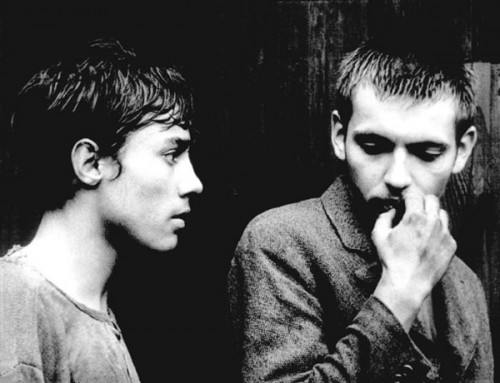

DIAMONDS OF THE NIGHT (Démanty noci, 1964)

Němec’s first feature length film follows the escape of two young concentration camp prisoners through the woods of Sudetenland and the ensuing pursuit of them.

DIAMONDS OF THE NIGHT (Démanty noci, 1964)

Němec’s first feature length film follows the escape of two young concentration camp prisoners through the woods of Sudetenland and the ensuing pursuit of them.

THE PARTY AND THE GUESTS (O slavnosti a hostech, 1966)

An examination of the mechanics of power and the ways people collaborate in the reality that oppresses them, the film follows a group of middle-aged bourgeois friends as they picnic in the woods on their way to a celebration.

THE PARTY AND THE GUESTS (O slavnosti a hostech, 1966)

An examination of the mechanics of power and the ways people collaborate in the reality that oppresses them, the film follows a group of middle-aged bourgeois friends as they picnic in the woods on their way to a celebration.

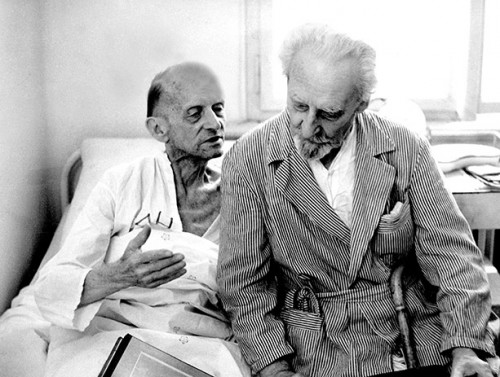

PEARLS OF THE DEEP (Perličky na dně, 1966)

A manifesto of the Czechoslovak New Wave, this anthology of five short films by five rising directors is based on a book by the celebrated writer Bohumil Hrabal.

PEARLS OF THE DEEP (Perličky na dně, 1966)

A manifesto of the Czechoslovak New Wave, this anthology of five short films by five rising directors is based on a book by the celebrated writer Bohumil Hrabal.

MARTYRS OF LOVE (Mučedníci lásky, 1967)

The most perfect embodiment of Němec’s vision of a film world independent of reality. Mounting a defense of timid, inhibited, clumsy, and unsuccessful individuals, the three protagonists are a complete antithesis of the industrious heroes of socialist aesthetics.

MARTYRS OF LOVE (Mučedníci lásky, 1967)

The most perfect embodiment of Němec’s vision of a film world independent of reality. Mounting a defense of timid, inhibited, clumsy, and unsuccessful individuals, the three protagonists are a complete antithesis of the industrious heroes of socialist aesthetics.

ORATORIO FOR PRAGUE (1968)

With film stock and camera at his disposal, director Němec was ready to document the invasion by Soviet tanks in August 1968, which crushed the democratization process of the so called Prague Spring.

ORATORIO FOR PRAGUE (1968)

With film stock and camera at his disposal, director Němec was ready to document the invasion by Soviet tanks in August 1968, which crushed the democratization process of the so called Prague Spring.

METAMORPHOSIS (Die Verwandlung, 1975)

Taking a typically personal approach, Němec depicts Samsa’s world through a subjective camera, emphasizing his inner world and his observation of shocked family and his surroundings.

METAMORPHOSIS (Die Verwandlung, 1975)

Taking a typically personal approach, Němec depicts Samsa’s world through a subjective camera, emphasizing his inner world and his observation of shocked family and his surroundings.

LATE NIGHT TALKS WITH MOTHER (Noční hovory s matkou, 2001)

Experimenting with digital video formats, this counterpart to Kafka’s Letter to Father finds the director probing his own psyche in the form of a confessional dialogue with his long deceased mother.

LATE NIGHT TALKS WITH MOTHER (Noční hovory s matkou, 2001)

Experimenting with digital video formats, this counterpart to Kafka’s Letter to Father finds the director probing his own psyche in the form of a confessional dialogue with his long deceased mother.

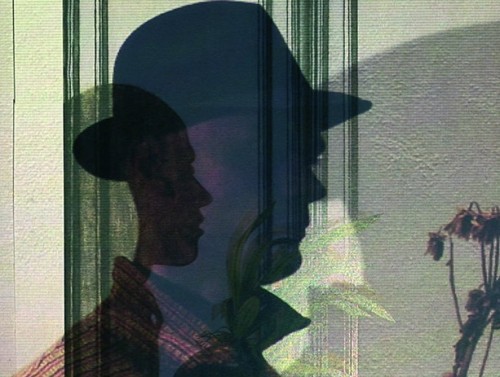

TOYEN (2005)

In one of the most enigmatic films of his career, Němec uses an abstract structure to create this portrait of revered Surrealist painter Toyen. The film, true to the subject’s own style, is an idiosyncratic vision that revisits the most oppressive period of her life.

TOYEN (2005)

In one of the most enigmatic films of his career, Němec uses an abstract structure to create this portrait of revered Surrealist painter Toyen. The film, true to the subject’s own style, is an idiosyncratic vision that revisits the most oppressive period of her life.

THE FERRARI DINO GIRL (Holka Ferrari Dino, 2009)

While shooting a documentary about the exciting and hopeful period known as the Prague Spring, Němec and his crew found themselves watching and filming in horror as the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

THE FERRARI DINO GIRL (Holka Ferrari Dino, 2009)

While shooting a documentary about the exciting and hopeful period known as the Prague Spring, Němec and his crew found themselves watching and filming in horror as the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

GOLDEN SIXTIES: JAN NĚMEC (Zlatá šedesátá, 2011, dir. Martin Šulík)

An illuminating portrait of Jan Němec from a 27-part TV series about masters of the Czechoslovak New Wave.

GOLDEN SIXTIES: JAN NĚMEC (Zlatá šedesátá, 2011, dir. Martin Šulík)

An illuminating portrait of Jan Němec from a 27-part TV series about masters of the Czechoslovak New Wave.

A LOAF OF BREAD (Sousto, 1960)

Němec’s graduation film follows the story of starving prisoners plotting to steal a piece of bread from a parked train in preparation for their escape.

A LOAF OF BREAD (Sousto, 1960)

Němec’s graduation film follows the story of starving prisoners plotting to steal a piece of bread from a parked train in preparation for their escape.

MOTHER AND SON (Moeder en zoon, 1967)

An absurdist tale about a doting mother of a brutal torturer.

MOTHER AND SON (Moeder en zoon, 1967)

An absurdist tale about a doting mother of a brutal torturer.

COMEBACK COMPANY

For press and booking inquiries:

To sign-up for our newsletter

email us with "newsletter" in the

subject line:

Comeback Company 2014

Design by Parallel Practice

© All rights reserved.