Minimum query is 3 letters.

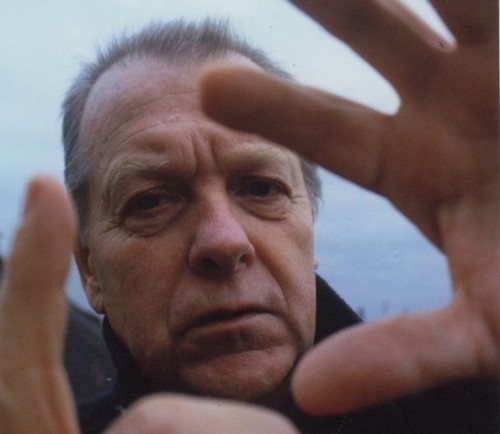

WHEN A FILM STARTS TO ASK FOR SOMETHING

Excerpts from Jan Němec’s extensive interview with critic Jiří Cieslar

ON THE COLLABORATION WITH ARNOŠT LUSTIG, the author of the original story:

"[…] I was an annoying nerd as a student, I just went to screenings and sat in libraries and took everything very seriously. I hoped that if I made cinema differently than what an ordinary student film usually looked like, the door to the professional world would be wide open for me. So I already thought about the theme for my graduation short film in my third year, that is the end of 1950s. “

“I had no respect for Czech literature or films, I devoured American authors, Hemingway and Faulkner. I was attracted to them for their strong subject matter: life is at stake there, they come from realism […] I was looking for an author and then the first books of Arnošt Lustig came out and became a sensation. He wrote about war very differently than you could read about it [in books by other Czech authors]. I did not even take notice he wrote Jewish stories; for me they were just strong dramas, through him finally available also in Czech literature. “

“[After the graduation film A Loaf of Bread also based on Lustig’s story] we chose with Arnošt another story from the same collection Diamonds of the Night – it was called Darkness Casts No Shadow, which is a much better title but Lustig wanted to use for the film the title of the collection because it was already known in the world as it was translated in many languages. And I obliged.”

“The concurrence of Diamonds and A Loaf of Bread is direct: in Loaf the boys are planning to escape and need bread, and Diamonds captures their escape. […] My work with Lustig took place on all levels – not like I took someone’s book and adapted it; he was present at all stages. But he also gave me complete freedom, he did not intervene during realization.”

“[…] the hallucinations in the book are very marginal, but I made them principal to the film: there are three levels – the current plot, memories, and then visions or hallucinations which all intertwine without any divisions or fade-over.” That results in uncertainty on which level you are presently. “Maybe because I had more sources. The starting point was a real story of three boys, who managed to escape in 1945 all the way to Prague. One of them was very sick and died two weeks after, but thankfully in a relative peace. During the film’s preparation Lustig gave me a diary of the sick boy. The diary captured the boy’s sort of hallucination which opened the door for the film style of Diamonds.” […] “that’s also why I leave the open ending, we don’t know how the boys ended up, although they probably are not shot – they are just going from nowhere to nowhere.”

ON OTHER INFLUENCES

“One of my influences was Robert Bresson. His film A Man Escaped (1956) overwhelmed me. I borrowed a 16mm print and an editing table and created a technical screenplay shot by shot.” I was inspired by “his attempt to make pure cinema, a pseudo documentary, without ‘moments’ for actors. It’s about longing for freedom, the victory of spirit, there is even Mozart in the score in the scene from the prison courtyard. […] I was impressed by the precise work with detail, exclusion of any theatricality, the use of non-actors, casting by type.”

“My second influence came from Alain Resnais and his films Hiroshima Mon Amour and Last Year in Marienbad. And of course Buñuel is directly quoted in Diamonds and the scene with ants.”

ON EDITING AND CREATING THE FEEL OF THE FILM IN THE EDITING ROOM

“Editor Miroslav Hájek worked probably on one third of the entire commercial production output of Barrandov Studios at that time, but he still found the time to work with us: he edited at the same time all of my films, films by Chytilova, Forman, from our first films, all the while when we all developed very different cinematographic styles. If you want to find something the films of the ‘new wave’ have in common, Hajek was one of the key personalities. Truly a genius of editing. […] He knew how to sense the various personalities of individual directors without one having to say a word to him. A virtuoso. We never lead any intellectual debates over the films. He just led me by his intuition to the final result. We were editingDiamonds almost five months. Without him I would have hardly thought of all the scale of possibilities the material was offering.”

ON THE COSTUME CHOICES and ESTER KRUMBACHOVÁ

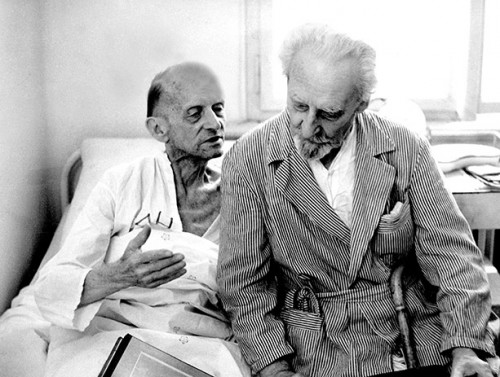

“Ester played a key role during production of the film. I met her on this film [and married her three years later], and apart from being a designer she became my dramaturge. She turned the costume choices into a key component of the story. Especially by refusing to use prisoner uniforms for the boys. They wear clothes that allow their body features to come through. Also there were no Nazi uniforms. The mark KL on the coats came from authentic photographs: Konzentration Lager. But the biggest Ester’s contribution was the hunt scene, where unknown old guys set on hunting the boys about whom they know nothing. […] With the old man scene Ester changed the entire screenplay, where originally it had only three pages and suddenly it became an extensive part of the film.”

ON THE CINEMATOGRAPHY

“I had the best possible crew. The DP was Jaroslav Kučera, we chose together the concept of hand held camera. Three cameramen took turns in carrying the heavy camera of those times through the woods – Kučera, Miroslav Ondříček, and Ivan Vojnár. It was part of the concept – sometimes the use of camera as an ‘objective’ viewer when it is steady by using tracks, sometimes expressing subjective feeling by a shaky handheld camera.” […] Kučera had to drop the project in the middle of the shooting period and “that’s when I asked Miroslav Ondříček, who was just assistant cameraman then, to take over. He made his famous films with Miloš Forman only after this. The last quarter of the film is all his. Against Kučera’s esthetes’ approach, he brought into Diamonds a sort of dynamism, naturalism.”

“I demanded [at the opening of the film] an unedited, more than two minute long shot; the boys run and fall down on the top of the hill as if dead. It’s the most expensive individual shot in the history of Czech cinema. [The tracks] construction took an entire month and we used up third of our budget on it. We made the shot in four takes although all of them ended up with mistakes.”

ON THE CAST

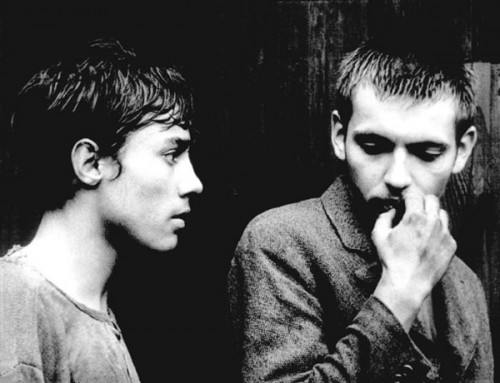

“I found Antonín Kumbera among extras in a short film of Evald Schorm. He was an uneducated railway man [with a very intelligent, contemplative face]. Originally the lead boy was supposed to be Ladislav Jánský, then a known photographer. But during the shoot Kumbera came to the forefront.” […] Neither of them made other films; Kumbera disappeared and Jánský emigrated to the United States and worked for Larry Flynt as an art director.

conducted in the fall of 1999 and published in a book of film essays titled CATS ON ATALANTA by Jiří Cieslar (Kočky na Atalantě, AMU, Prague, 2003)

DIAMONDS OF THE NIGHT (Démanty noci, 1964)

Němec’s first feature length film follows the escape of two young concentration camp prisoners through the woods of Sudetenland and the ensuing pursuit of them.

DIAMONDS OF THE NIGHT (Démanty noci, 1964)

Němec’s first feature length film follows the escape of two young concentration camp prisoners through the woods of Sudetenland and the ensuing pursuit of them.

THE PARTY AND THE GUESTS (O slavnosti a hostech, 1966)

An examination of the mechanics of power and the ways people collaborate in the reality that oppresses them, the film follows a group of middle-aged bourgeois friends as they picnic in the woods on their way to a celebration.

THE PARTY AND THE GUESTS (O slavnosti a hostech, 1966)

An examination of the mechanics of power and the ways people collaborate in the reality that oppresses them, the film follows a group of middle-aged bourgeois friends as they picnic in the woods on their way to a celebration.

PEARLS OF THE DEEP (Perličky na dně, 1966)

A manifesto of the Czechoslovak New Wave, this anthology of five short films by five rising directors is based on a book by the celebrated writer Bohumil Hrabal.

PEARLS OF THE DEEP (Perličky na dně, 1966)

A manifesto of the Czechoslovak New Wave, this anthology of five short films by five rising directors is based on a book by the celebrated writer Bohumil Hrabal.

MARTYRS OF LOVE (Mučedníci lásky, 1967)

The most perfect embodiment of Němec’s vision of a film world independent of reality. Mounting a defense of timid, inhibited, clumsy, and unsuccessful individuals, the three protagonists are a complete antithesis of the industrious heroes of socialist aesthetics.

MARTYRS OF LOVE (Mučedníci lásky, 1967)

The most perfect embodiment of Němec’s vision of a film world independent of reality. Mounting a defense of timid, inhibited, clumsy, and unsuccessful individuals, the three protagonists are a complete antithesis of the industrious heroes of socialist aesthetics.

ORATORIO FOR PRAGUE (1968)

With film stock and camera at his disposal, director Němec was ready to document the invasion by Soviet tanks in August 1968, which crushed the democratization process of the so called Prague Spring.

ORATORIO FOR PRAGUE (1968)

With film stock and camera at his disposal, director Němec was ready to document the invasion by Soviet tanks in August 1968, which crushed the democratization process of the so called Prague Spring.

METAMORPHOSIS (Die Verwandlung, 1975)

Taking a typically personal approach, Němec depicts Samsa’s world through a subjective camera, emphasizing his inner world and his observation of shocked family and his surroundings.

METAMORPHOSIS (Die Verwandlung, 1975)

Taking a typically personal approach, Němec depicts Samsa’s world through a subjective camera, emphasizing his inner world and his observation of shocked family and his surroundings.

LATE NIGHT TALKS WITH MOTHER (Noční hovory s matkou, 2001)

Experimenting with digital video formats, this counterpart to Kafka’s Letter to Father finds the director probing his own psyche in the form of a confessional dialogue with his long deceased mother.

LATE NIGHT TALKS WITH MOTHER (Noční hovory s matkou, 2001)

Experimenting with digital video formats, this counterpart to Kafka’s Letter to Father finds the director probing his own psyche in the form of a confessional dialogue with his long deceased mother.

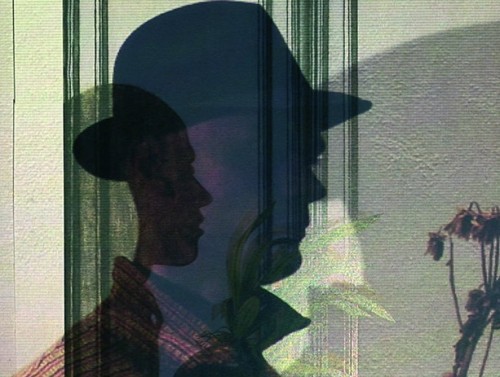

TOYEN (2005)

In one of the most enigmatic films of his career, Němec uses an abstract structure to create this portrait of revered Surrealist painter Toyen. The film, true to the subject’s own style, is an idiosyncratic vision that revisits the most oppressive period of her life.

TOYEN (2005)

In one of the most enigmatic films of his career, Němec uses an abstract structure to create this portrait of revered Surrealist painter Toyen. The film, true to the subject’s own style, is an idiosyncratic vision that revisits the most oppressive period of her life.

THE FERRARI DINO GIRL (Holka Ferrari Dino, 2009)

While shooting a documentary about the exciting and hopeful period known as the Prague Spring, Němec and his crew found themselves watching and filming in horror as the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

THE FERRARI DINO GIRL (Holka Ferrari Dino, 2009)

While shooting a documentary about the exciting and hopeful period known as the Prague Spring, Němec and his crew found themselves watching and filming in horror as the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

GOLDEN SIXTIES: JAN NĚMEC (Zlatá šedesátá, 2011, dir. Martin Šulík)

An illuminating portrait of Jan Němec from a 27-part TV series about masters of the Czechoslovak New Wave.

GOLDEN SIXTIES: JAN NĚMEC (Zlatá šedesátá, 2011, dir. Martin Šulík)

An illuminating portrait of Jan Němec from a 27-part TV series about masters of the Czechoslovak New Wave.

A LOAF OF BREAD (Sousto, 1960)

Němec’s graduation film follows the story of starving prisoners plotting to steal a piece of bread from a parked train in preparation for their escape.

A LOAF OF BREAD (Sousto, 1960)

Němec’s graduation film follows the story of starving prisoners plotting to steal a piece of bread from a parked train in preparation for their escape.

MOTHER AND SON (Moeder en zoon, 1967)

An absurdist tale about a doting mother of a brutal torturer.

MOTHER AND SON (Moeder en zoon, 1967)

An absurdist tale about a doting mother of a brutal torturer.

COMEBACK COMPANY

For press and booking inquiries:

To sign-up for our newsletter

email us with "newsletter" in the

subject line:

Comeback Company 2014

Design by Parallel Practice

© All rights reserved.