Minimum query is 3 letters.

JAN NĚMEC: HOTEL CALIFORNIA II

Blue sky sickness, that’s it. You lie down for a little nap one hot afternoon and wake up a few hours later to find ten years have passed you by.

That four hundred thousand dollars never did turn up in my account, so I told myself, Take it easy, and cleared out the basement room at my friend Kevin’s house. “You can live there for free if you want,” he had said. It was nothing much: a wooden floor with one window and a door with a padlock on it. But the moment you opened that door, your nostrils were flooded with the smell of the warm sea, just twenty yards away. A few barefoot steps in your shorts and you were wrestling with the Pacific waves.

It isn’t hard to furnish the place. Thursdays are garbage day in Hermosa Beach. People put whatever they don’t need out on the curb, and they’re moving in and out all the time, so on any given Thursday you can find chairs, dressers, mirrors, hotplates, pots and pans, frames, even pictures, no problem. Nothing’s a problem here. Need a phone? I worked out of two phone booths each morning from 10 to noon, for free. Breakfast? Coffee and pastry buffet at the local Wells Fargo branch, also for free. Transportation? The bike on the corner or rentals a dollar apiece, for wherever the bus didn’t go. And Kevin’s Triumph TR3 convertible, rain or shine. No true Californian can do without his convertible. I even convinced him to change the license plate to NA-SRAT — kind of a Czech equivalent of FUK-OFF. You can choose any word you want here for your license plate, as long as it isn’t a swear word. Fooled them on that one! I wonder how the border patrol back home would react? Anyway, from then on my life was just writing, the sound of the sea, and the stereos from my three neighbors. Perfect. The less you have, the freer you are. A slight incident on my way home, though: We’d been drinking tequila, which is made from the mescaline cactus and has an amazing effect on the brain during interrogations with the LAPD, or, as the case may be, psychiatrists at the military hospital in Prague. You get drunk and high at the same time. So instead of heading toward the sea, I tried to take a shortcut and got swallowed up in ugly downtown LA.

The police said they entertained themselves watching me for a while before they arrested me, wondering if I would crash as I drove down the wrong side of the road, singing at the top of my lungs and clapping my hands over my head while I steered with my knees. They asked what drug I was on, and when I said tequila they were kind enough to explain what I just told you about the cactus and the mescaline. I told them I was afraid they were going to beat me up, because of all the stories I’d read about police brutality. But one of the muscular officers in his chic uniform said, No, no, this is what we’re here for, and pointed to the slogan on the door of his police car: “To protect and serve.” The truth is they treated me with kid gloves, maybe because I was in a part of town where most people they stopped were likely to pull a gun or a knife on them.

Anyhow, they locked me up in the city jail and said the next morning I would go before a judge, where I could plead innocent, or guilty and accept the verdict. There were about two hundred of us in a big holding cell underground. I was kind of a novelty since I was the only white guy, and eccentrically dressed in a blue blazer from Pierre Cardin to boot. (What nobody knew, of course, was I had bought it for three bucks at a Salvation Army.) The other prisoners looked at me like I’d landed there from the moon.

At six a.m. the next day, they rolled up a metal blind to reveal a podium at the front of the room. The court officer told us all to rise and prepare to state our case to his honor the judge.

“Excuse me, your honor, esquire, sir,” a black man shouted, “but this isn’t a courtroom, this is a fucking garage!”

The room exploded in applause. It may not have been very tactful to point out that the temporary courtroom was actually a garage, but the judge seemed to take it in stride. “Well, anyone who doesn’t like it herecan go spend a pleasant week in the county penitentiary and then comeback and see me.” The defendants rewarded his democratic proposal with another round of applause.

It made for a bizarre show. Ragged, drunken, battered, stoned vagabonds of every race stood, one by one, as their names were called out, teetering, barely able to stand on their feet. Some responded while lying on the floor, which wasn’t considered polite, so they were raised to an upright position. Most of them had been here plenty of times before: vandalism, drunk driving, assault and battery, murder, you name it.

“Yes, your honor,” they addressed the judge politely. The ones who’d been brought in on minor violations usually shouted “Guilty!” when asked for their plea, to speed the process up. It was a bizarre ritual, a ceremony of street people with the honorable judge at its head. The whole thing felt like some strange game fixed in advance, both sides respecting the rules with a heavy dose of gallows humor. In most cases the judge handed down his verdict without a second thought, the crowd assessinghis performance with appreciative grumbling or jeers and whistles, just like at a baseball game.

I was assessed a fine of $680 — or, since this was my first offense for DUI, I could attend a night school program. The judge accepted my request to attend the school in Beverly Hills. “I would feel better there,” I said. Everyone in the room who wasn’t white reacted to my open display of racism by whistling, stomping the floor, and threatening to lynch me.

Before we left they handcuffed us together in threes, and as we walked out of the room an Asian man accused of murder offered me $20,000 to trade coats with him. He said he would have an easier time escaping in my blue Pierre Cardin blazer than in his blood-stained jacket. “Take it,” said my other partner in crime. “He’ll keep his promise. That’s the only law us prisoners follow. Helping somebody escape is a matter of honor.”

The Traffic School in Beverly Hills was a great place to make connections. It was a real upper-crust crowd, only instead of getting together for a party, they were there because they’d all been arrested at the same time, and since everything in America is about business, the place was filled with men and women exchanging business cards, talking up plans for their next big deal, and in general socializing and chatting away about everything and anything but the dangers of alcohol. Nobody paid the slightest attention to the lectures.

I was the only social climber in this bunch. I fell into conversation with a big-shot professor from UCLA and tried to sell him on my theory that none of us was really responsible for our dependence on alcohol. “When a little kid cries,” I said, “his parents stick a lollipop or a piece of candy in his mouth, maybe a chocolate bar, and the kid calms down, smiles like an idiot, and leaves them alone. When he gets older they use cake or ice cream. Well, alcohol is 20 percent sugar, so it’s like the same thing, we’ve still got the same bad habit, the same addiction to sugar, that our parents forced on us when we were little.” The professor didn’t buy it. Clearly I wasn’t going to make it in this country as a scientist, so I went back to my original plan of making money in business.

One of my semi-successes was a screening of my gruesome thriller The Czech Connection, projected into the sky above Hermosa Beach. I borrowed a 16-millimeter projector from the local library — for free! — and passed around a hat for donations. Originally I wanted to show it against the back wall of the Lighthouse Café, the legendary jazz club, but that night the fog was unusually thick and it stuck right to the roofs of the buildings, which are all really low in Hermosa Beach. So I pulled a typical Czech improvisation and just pointed the camera up in the air, over the wall and into the fog. The effect was spectacular. Instead of just bouncing off the one-dimensional surface of a wall or a screen, the beam of light played across the fog’s constantly shifting shapes, circling, climbing, dropping. As the images from the film, which is a vision of my own death — I particularly recommend the autopsy scene, where they take out my brain and replace it with old newspapers — rolled across the sky like a desert mirage, the audience was so excited they practically fell over themselves to drop their coins and bills in the hat. Of course the omnipresent and ever-efficient LAPD were quick to turn up. Fortunately it wasn’t child pornography descending from the heavens or I’d probably still be stuck in state prison. The officers didn’t mind the sight of the rippling brain on the autopsy room scales, but my little film production company didn’t have a permit to screen its works in public.

I had to shut off the projector, but the money stayed with me. I got off with an official reprimand while the crowd started chanting, “Police brutality!” and invoking their rights to see whatever they wanted. I used the money to pay part of the fine for my DUI, and the next night went to Santa Monica and fished quarters out of a fountain with a coathanger. Tourists throw them in and make a wish that they’ll come back someday. The police there knew me by now. In fact they knew me so well they hung on to my ankles so I wouldn’t fall in. They were just glad to have somebody cleaning out the fountain without the city having to pay.

I needed the coins for my office — the two phone booths on the beach, where I worked diligently from 10 a.m. to noon every day. You could get a call from literally anywhere in the world on those phones, and if both phones rang at once I would just hand one of them to my “secretary,” a girl on roller skates who happened to be going by. “Tell them your boss is on the other line!” I would whisper, cupping my hand over the mouthpiece.

My work paid off. One day the phone in the right-hand booth rang and I picked it up to discover I had a check for $30,000 waiting for me, the seed funding for my next business project.

So I hopped on a bike and pedaled over to the bank. As usual it was one without brakes — what did you need brakes for when the seaside trails were so flat? If I needed to stop, I just put my feet down. I propped my raven steed against the wall next to the entrance, strode in for my usual free morning coffee, then stepped up to the cashier’s window and said politely: “Hello. Could you tell me how much money I have in my account today?”

The cashier smiled. She knew me well, and she knew I liked to play this game. She tapped a few keys on her keyboard and answered: “The same as yesterday, Mr. Nemec. Three dollars and twenty cents.”

“Well, I have a check here I’d like to deposit.”

When I slid the check for $30,000 across the counter to her, she gave me a long look, smiled again, though in a slightly different way than usual, and said: “Just a moment please, Mr. Nemec.”

She walked over to the office of the branch manager. Dressed in an immaculate shirt and tie, he looked every part the banker — unlike the rest of the staff, who still felt an attachment to the local beach community. The gentleman rose from his seat and came over to greet me. “Mr. Nemec. We like you very much. You’re very friendly and polite, and please, feel free to keep coming for coffee every day, but don’t make me call the police. Forging checks is a very serious crime. I’m going to take it as a poor attempt at a joke. I’m going to tear up your check and forget it ever happened, but you have to promise me you won’t ever try such a childish trick again.”

“Stop! Stop! Stop!” . . . in the name of love . . . I shouted the words from the famous Supremes song. Luckily I was able to stop the manager from tearing it up, but it took me three weeks to round up all the documents I needed to prove to him the check was real.

Once the money was deposited in my account, I went and stood in line for two days at the INS, the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Finally it was my turn. I showed the officer all my expired and useless forms of ID, and he just asked, matter-of-factly: “What sort of visa did you use to enter the US?”

“A B1, valid for three weeks,” I answered honestly.

“And what is your current status?”

“I decided to extend my visit, so I actually overstayed by a little.”

“How many weeks?” the officer asked.

My answer took him by surprise: “To be totally honest, seven years.”

The officer shook his head. This sort of thing was normal coming from Mexicans or Puerto Ricans, but from a white man, a European who claims to be educated and highly skilled? He’d never seen that before. He balked.

Of course this wasn’t my first run-in with the U.S. immigration authorities. Ages ago I had requested special permission to stay in the country from the U.S. Secretary of Justice. After a while, the Justice Department responded that I might have a chance if I were a citizen of Iran, but not otherwise. This was two weeks after Muslim fanatics took Americans hostage at the U.S. embassy in Tehran. In my letter to the secretary I had clearly stated that I was from Czechoslovakia and had been driven out of my country by the invasion of Soviet tanks. Bureaucrats are the same everywhere, even at the highest levels in Washington, DC.

I also had an interesting conversation at the immigration office when they asked whether I had been a member of the Communist Party in Czechoslovakia. I suddenly realized it actually wasn’t easy to prove that you weren’t a communist. Anyone could say it.

The immigration officer pushed: “You must have been at least in the children’s organization, where they wear the red scarfs, and the teenagers’ group, with the blue shirts.”

“I’ll admit I was a candidate for membership in the Pioneers and for the Union of Youth, but I never got a red scarf or a youth union membership card,” I said. I was lying of course.

“Then how did you rise to such a high-profile position in the film industry? Everybody knows you had to be a Communist to do that.”

“Yes and no,” I said. “I was never accepted to the youth organizations because of my so-called antisocial behavior.”

“Aha,” the officer said, thinking he had me trapped. “So you have a criminal record! You realize of course we don’t let criminals into this country.”

I tried to explain that I couldn’t submit proof of my lack of criminal record, since I had been stripped of my Czechoslovak citizenship and therefore didn’t exist anymore in the state’s official records. The officer wasn’t pleased. I wasn’t applying for political asylum, so naturally he assumed I was just a slick communist agent.

Only later did I realize that it might have been because of Věra, a fun-loving Czech ladyfriend of mine, who rented a fancy high-rise apartment in Santa Monica, right on the beach. How could she afford it? Nobody knew, but she had a lot of important visitors. High rollers from TRW and Lockheed, corporations working on top-secret aviation and aerospace projects to guarantee U.S. dominance over the Soviets. While she pretended to be drunk, smashing glasses under her high heels as she danced on the tabletop, she was quietly filing away in her brain which engineers were, as she put it, “ripe,” meaning ripe for our dear country’s spies.

Just imagine it: A rocket lifts off from Cape Canaveral, carrying enough nuclear bombs to light us up like they did in Hiroshima, where people were reduced to nothing but shadows on the wall. The U.S. rocketgoes sailing across the sky, when suddenly — a tiny error. Instead of hitting us Czechs, it comes down on California. Věra, acting drunk, gave the main engineer on the project a night of lovemaking that most American men can only dream of, and the next day the engineer was a bit out ofwhack, causing the rocket to hit a different target than intended.

The INS officer snapped shut the thick notebook holding my files and I was back on the beach at the Hotel California. The people from the organization who had fed me the 30K ran out of steam. The film wasn’t happening. So I hopped back on the seat of another abandoned bicycle leaning against the wall of the bank and peddled off down the empty, carefree path along the Pacific.

__

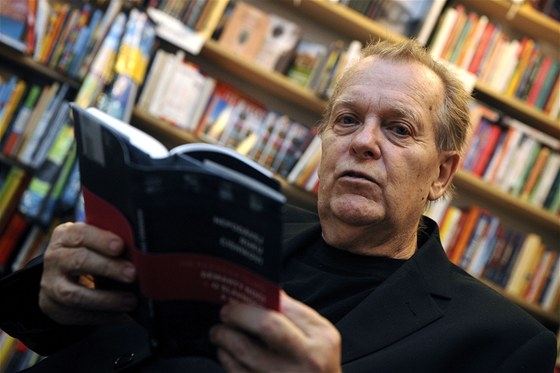

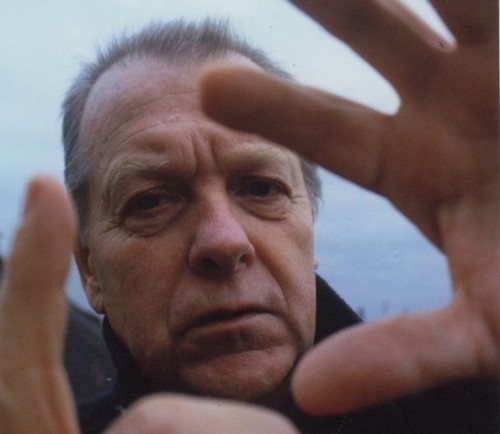

(filmmaker's photo portrait: ČTK)

From the book DON'T SHAKE HANDS WITH THE WAITER (Nepodávej ruku číšníkovi, 2011), by Jan Němec

Translated from the Czech by Alex Zucker

The book is autobiographical and Chapter 24: HOTEL CALIFORNIA II takes place roughly in mid 1980s when Němec lived in exile in the U.S.

Published and translated with the permission of the author and Torst publishers © 2011.

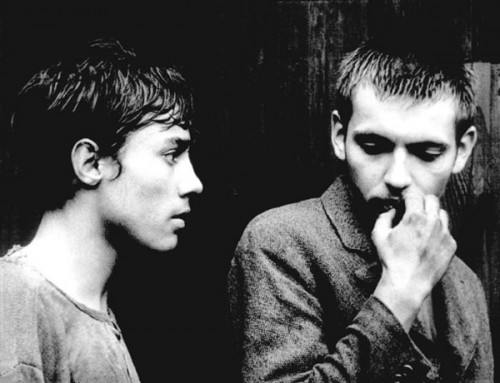

DIAMONDS OF THE NIGHT (Démanty noci, 1964)

Němec’s first feature length film follows the escape of two young concentration camp prisoners through the woods of Sudetenland and the ensuing pursuit of them.

DIAMONDS OF THE NIGHT (Démanty noci, 1964)

Němec’s first feature length film follows the escape of two young concentration camp prisoners through the woods of Sudetenland and the ensuing pursuit of them.

THE PARTY AND THE GUESTS (O slavnosti a hostech, 1966)

An examination of the mechanics of power and the ways people collaborate in the reality that oppresses them, the film follows a group of middle-aged bourgeois friends as they picnic in the woods on their way to a celebration.

THE PARTY AND THE GUESTS (O slavnosti a hostech, 1966)

An examination of the mechanics of power and the ways people collaborate in the reality that oppresses them, the film follows a group of middle-aged bourgeois friends as they picnic in the woods on their way to a celebration.

PEARLS OF THE DEEP (Perličky na dně, 1966)

A manifesto of the Czechoslovak New Wave, this anthology of five short films by five rising directors is based on a book by the celebrated writer Bohumil Hrabal.

PEARLS OF THE DEEP (Perličky na dně, 1966)

A manifesto of the Czechoslovak New Wave, this anthology of five short films by five rising directors is based on a book by the celebrated writer Bohumil Hrabal.

MARTYRS OF LOVE (Mučedníci lásky, 1967)

The most perfect embodiment of Němec’s vision of a film world independent of reality. Mounting a defense of timid, inhibited, clumsy, and unsuccessful individuals, the three protagonists are a complete antithesis of the industrious heroes of socialist aesthetics.

MARTYRS OF LOVE (Mučedníci lásky, 1967)

The most perfect embodiment of Němec’s vision of a film world independent of reality. Mounting a defense of timid, inhibited, clumsy, and unsuccessful individuals, the three protagonists are a complete antithesis of the industrious heroes of socialist aesthetics.

ORATORIO FOR PRAGUE (1968)

With film stock and camera at his disposal, director Němec was ready to document the invasion by Soviet tanks in August 1968, which crushed the democratization process of the so called Prague Spring.

ORATORIO FOR PRAGUE (1968)

With film stock and camera at his disposal, director Němec was ready to document the invasion by Soviet tanks in August 1968, which crushed the democratization process of the so called Prague Spring.

METAMORPHOSIS (Die Verwandlung, 1975)

Taking a typically personal approach, Němec depicts Samsa’s world through a subjective camera, emphasizing his inner world and his observation of shocked family and his surroundings.

METAMORPHOSIS (Die Verwandlung, 1975)

Taking a typically personal approach, Němec depicts Samsa’s world through a subjective camera, emphasizing his inner world and his observation of shocked family and his surroundings.

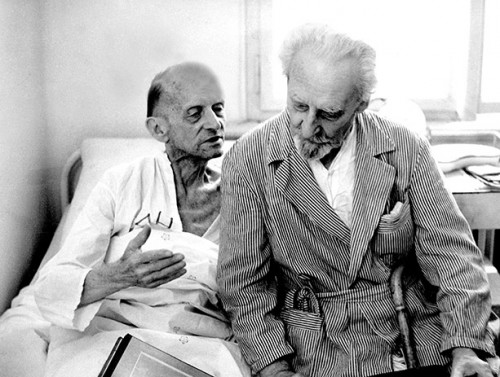

LATE NIGHT TALKS WITH MOTHER (Noční hovory s matkou, 2001)

Experimenting with digital video formats, this counterpart to Kafka’s Letter to Father finds the director probing his own psyche in the form of a confessional dialogue with his long deceased mother.

LATE NIGHT TALKS WITH MOTHER (Noční hovory s matkou, 2001)

Experimenting with digital video formats, this counterpart to Kafka’s Letter to Father finds the director probing his own psyche in the form of a confessional dialogue with his long deceased mother.

TOYEN (2005)

In one of the most enigmatic films of his career, Němec uses an abstract structure to create this portrait of revered Surrealist painter Toyen. The film, true to the subject’s own style, is an idiosyncratic vision that revisits the most oppressive period of her life.

TOYEN (2005)

In one of the most enigmatic films of his career, Němec uses an abstract structure to create this portrait of revered Surrealist painter Toyen. The film, true to the subject’s own style, is an idiosyncratic vision that revisits the most oppressive period of her life.

THE FERRARI DINO GIRL (Holka Ferrari Dino, 2009)

While shooting a documentary about the exciting and hopeful period known as the Prague Spring, Němec and his crew found themselves watching and filming in horror as the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

THE FERRARI DINO GIRL (Holka Ferrari Dino, 2009)

While shooting a documentary about the exciting and hopeful period known as the Prague Spring, Němec and his crew found themselves watching and filming in horror as the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

GOLDEN SIXTIES: JAN NĚMEC (Zlatá šedesátá, 2011, dir. Martin Šulík)

An illuminating portrait of Jan Němec from a 27-part TV series about masters of the Czechoslovak New Wave.

GOLDEN SIXTIES: JAN NĚMEC (Zlatá šedesátá, 2011, dir. Martin Šulík)

An illuminating portrait of Jan Němec from a 27-part TV series about masters of the Czechoslovak New Wave.

A LOAF OF BREAD (Sousto, 1960)

Němec’s graduation film follows the story of starving prisoners plotting to steal a piece of bread from a parked train in preparation for their escape.

A LOAF OF BREAD (Sousto, 1960)

Němec’s graduation film follows the story of starving prisoners plotting to steal a piece of bread from a parked train in preparation for their escape.

MOTHER AND SON (Moeder en zoon, 1967)

An absurdist tale about a doting mother of a brutal torturer.

MOTHER AND SON (Moeder en zoon, 1967)

An absurdist tale about a doting mother of a brutal torturer.

COMEBACK COMPANY

For press and booking inquiries:

To sign-up for our newsletter

email us with "newsletter" in the

subject line:

Comeback Company 2014

Design by Parallel Practice

© All rights reserved.